Culture as the most enduring bridge between Poland and Egypt

The history of Polish-Egyptian relations has roots deeper than it may appear. Long before the signing of the first diplomatic agreements, before the visits of official delegations and contemporary academic exchanges, the bond between the two nations was culture: the language of art, science and shared admiration for the heritage of the civilization on the Nile. From the romantic journeys of Juliusz Słowacki, through the fascination with the Orient in Polish painting and literature, to the scientific expeditions of Kazimierz Michałowski and the work of modern institutions, Egypt holds a special place in the Polish imagination. It is precisely through culture that Poles and Egyptians have been able to get to know, understand and inspire one another. Art, science and education have proved more durable than borders, ideologies or political systems. The encounter between Europe and Egypt – two different yet complementary worlds – resulted in a dialogue in which fascination with history, spirituality and art replaced political divides. Upon this foundation grew a bridge of mutual understanding that has endured across eras and systems. Romantic beginnings – Słowacki on the Nile Before the artists and scholars of the nineteenth century arrived on the Nile, Poles whose presence had religious, military and humanistic dimensions had already reached Egypt. Among the earliest Poles to arrive were missionaries and pilgrims who, by leaving accounts of their journeys to the holy places, opened the first pages of the shared cultural history of Poland and Egypt. Another significant group of Poles who appeared on the Nile and left their mark on history were the legionnaires who reached Egypt with Napoleon. Among them stands out Salomon Horowitz, a Jew probably from Lublin, an intellectual who served in Napoleon’s army, including as a translator. He was also involved in arranging collections, copying Arabic and Hebrew texts, and cooperating with scholars who later created the famous Description de l’Égypte. Horowitz symbolically represents the presence of Poles in the intellectual culture of the Napoleonic era, people of knowledge and letters, not only arms. His activity constitutes the first example of a Pole participating in the documentation and popularisation of Egyptian heritage in Europe. At the same time, soldiers such as Józef Szumlański left memoirs describing Cairo, Alexandria and the pyramids. In their accounts, Egypt appears as a land astonishing and different, yet evoking respect and admiration. Together with the notes of pilgrims and missionaries, they created the first circle of Polish testimonies about Egypt, documenting not only the country but also the process of encounter between two cultural worlds. On this foundation, in the mid-nineteenth century, a new type of Polish presence in Egypt emerged which had a great influence on Polish literature: the romantic journey, combining the curiosity of a scholar with the spiritual reflection of an artist. Juliusz Słowacki, who visited Alexandria and Cairo in 1836–1837, belonged to the first generation of Polish creators for whom Egypt was not only an exotic destination but a space for philosophical reflection on time, memory and the endurance of nations. In the poem Piramidy, the poet described the moment of climbing to the top of the Great Pyramid of Cheops, an experience that became for him a symbol of spiritual elevation. In his gaze upon the desert and the Nile he saw not only the beauty of nature, but also a metaphor of human immortality and national survival. For Słowacki, Egypt was a place where history becomes eternity and stone becomes a prayer. Artists and scholars on the Nile In the second half of the nineteenth century, Egypt became for Poles not only a destination for spiritual journeys but also a scientific laboratory and a source of artistic inspiration. Doctors, botanists, painters, photographers and writers arrived on the Nile, driven not by the desire merely to observe but to understand—to study the history, nature and culture of the country and incorporate it into the European circulation of knowledge. Among the best known were: Ignacy Żagiell (1826–1891), a physician and traveller from the Vilnius region who studied in Kyiv, is among the pioneers of Polish Egyptology. He spent several years in Egypt, reaching as far as Nubia and Ethiopia. His extensive Historia starożytnego Egiptu (History of Ancient Egypt, 1880) was one of the first attempts to popularise knowledge of the pharaohs in the Polish language. It combined erudition with the romantic passion of an explorer and for many years served as a primary source of knowledge about Egypt for Polish readers. A little earlier, Leon Cienkowski (1822–1887), a botanist and microbiologist, was invited by the Egyptian authorities to collaborate on research into the flora of the Nile Delta. In his reports he described vegetation, climatic conditions and issues related to Egypt’s water management.Meanwhile, Łukasz Dobrzański (1864–1909), a photographer and illustrator, was one of the first Poles who attempted to capture Egypt through the lens. His photographs of the Nile, Giza and Thebes constitute today an invaluable iconographic source and at the same time evidence that fascination with the Orient had moved from literature into a new medium—photography. On the same foundation developed the work of painters who gave Egypt an artistic and spiritual dimension. Franciszek Tepa (1828–1889), a graduate of the Kraków Academy, travelled to Egypt and Syria in the 1860s. His watercolours from Giza, Cairo and the Nile Valley, depicting pyramids, mosques and the daily life of Egyptians, combined realism with a lyrical atmosphere and were among the first works on Oriental themes in Polish painting. For Tepa, Egypt was not an exotic backdrop but a living world in which history and the present meet. A similar spirit accompanied Izydor Jabłoński (1835–1905), a friend and biographer of Jan Matejko, who painted genre scenes from Cairo and the desert, and Stanisław Chlebowski (1835–1884), court painter to Sultan Abdülaziz in Constantinople, who visited Egypt many times. At the turn of the century, a new quality was introduced by Edward Okuń (1872–1945), a modernist painter who travelled to the Nile to create illustrations for Pharaoh by Bolesław Prus. This project was

The future of cooperation between Lebanon and Poland

The positive experience from the ongoing Polish-Lebanese cooperation is a good prognosis for the future. Current areas of cooperation, such as humanitarian and development aid and security, should be deepened, and cooperation should also be extended to new areas. As the leader of Central and Eastern Europe, Poland has a lot to offer Lebanon on many levels. Currently, Poland is the 20th largest economy in the world, which is the result of a successful political and economic transformation. Thanks to dynamic development over the last two decades, Poland has become a key European Union country, possessing modern road and rail infrastructure, enjoying the reputation of being one of the safest countries in Europe, and attracting investors from around the world. Polish cities, including provincial ones, have undergone a metamorphosis, renovating homes, roads, and public utility buildings. The non-governmental organization sector is also thriving, which is evidence of a well-developed civil society. Lebanon needs similar reforms, and Poland can help it, especially since it shares similar experiences of foreign occupation and the fight for sovereignty and democracy. Therefore, Poland, which has no colonial baggage, is an ideal partner for Lebanon in terms of scientific and civil cooperation, as well as in the security and economic-development dimensions. Political Transformation and Scientific-Academic Cooperation Lebanon needs reforms similar to those that Poland successfully introduced as part of its systemic transformation. While Lebanon has institutions of a democratic state, elections are held, and there is no authoritarian system like in Poland before 1989, it is necessary to strengthen civic awareness, national cohesion, sovereignty, and good governance, as well as to strengthen state institutions and combat corruption. Poland has rich experience in this area that it can share. This concerns both the institutional improvement of bodies responsible for fighting corruption, organized crime, banking supervision, or the judiciary, as well as cooperation between non-governmental organizations, including those working for good governance, civil society, digital education, combating disinformation, election monitoring, and media freedom. In this regard, it is necessary to intensify expert-level cooperation, including joint workshops and training, as well as the organization and participation in conferences (e.g., participation of Lebanese experts and politicians in the Warsaw Security Forum, organized by the Casimir Pulaski Foundation). One platform for cooperation could be the Shaffafiya portal as a place for the exchange of opinions and analyses by experts from Poland, Lebanon and other countries in Eastern Europe and the Middle East. Expert and institutional cooperation should be accompanied by the intensification of academic relations and the development of joint research projects. In this area, Poland can offer Lebanese students attractive study conditions at Polish universities using instruments such as Erasmus+, the Ignacy Łukasiewicz Scholarship Program for engineering students, and the Stefan Banach Scholarship Program for medical students. All these instruments are already available to Lebanese students. It would also be advisable to stimulate lecturer mobility between Lebanon and Poland, which would also foster the development of joint research projects and scientific publications. Furthermore, Polish specialists, particularly archaeologists, can play an important role in the protection of historical monuments in Lebanon. In this regard, Poland offers Lebanon unique knowledge in the field of historical monument conservation, which is crucial for Lebanese tourism. Infrastructure and Transport Poland has vast and recent experience in the expansion and modernization of railway infrastructure and public transport (metro, bus, and tram networks). Lebanon, on the other hand, faces problems with traffic jams, a lack of railways, and a poor and unintegrated public transport system. The old Lebanese railway line has been out of service for a long time, although its reconstruction is an urgent necessity. Intercity connections are provided exclusively by taxis and minibuses, which are also the only means of public transport in perpetually congested Beirut. Poland has both the know-how in urban transport planning and the capabilities and experience in the construction of rolling stock and transport infrastructure. Poland can therefore play a key role in reforming the transport system in Beirut, including the design of a tram and metro network. The experience of the company Metroprojekt, which was the main designer of the Warsaw Metro, can be crucial, as it is recent and was associated with complex underground conditions and implementation in a highly built-up area with heavy traffic. This is precisely what Beirut needs. Poland can also offer advice on creating modern public transport authorities responsible for fare and timetable integration (buses, trams, metro). The offer may also include training for engineers and planners on optimizing the transport network and implementing passenger information systems (display boards, applications), as well as launching student and engineer exchange programs with the Warsaw University of Technology and the Cracow University of Technology to train local specialists in metro construction, tunneling, and traffic management. Poland can also present a broad offer for the supply of modern rolling stock that is competitively priced and adapted to difficult conditions. Poland is a leader in this field. This includes, among others, Solaris buses, which is a leading city bus manufacturer in Europe and has introduced low-floor buses to cities in Poland and Europe. Solaris is also a leader in the segment of electric and hydrogen buses, which corresponds to global trends. The Polish bus offer includes both city and intercity buses, with other manufacturers being Autosan and NesoBus. The former, besides city buses, also offers medium-sized intercity buses, ideal for short routes. NesoBus, in turn, offers modern hydrogen buses. Beirut should also consider introducing trams to its streets, and Poland also has recent and rich experience in this case. After a period of liquidating tram lines, as part of a mistaken trend at the end of the 20th century, Poland has recently embarked on the dynamic expansion and modernization of tram lines. Currently, their total length in Poland is over 2400 km, and the tram networks in Warsaw and the Katowice agglomeration are among the largest and most modern in Europe. Polish companies Modertrans and Pesa can offer the most modern tram rolling stock, which can now be seen

Railway modernization and public transport – the Polish model and offer for Iraq

Poland has extensive experience in modernizing its rail network as well as expanding public transport in cities and Iraq’s needs in this area are immense. Public transport is based almost exclusively on shared taxis and minibuses; there is no metro or trams, and the only operational railway line, connecting Basra with Baghdad, is outdated. The expansion of the public transport network in Baghdad would not only solve the issue of gigantic traffic jams hindering movement but would also contribute to improving air quality and, consequently, public health. The 8-million-strong Baghdad, which is currently undergoing dynamic development and expansion, cannot afford to continue functioning without a metro, trams, and buses. Poland, in turn, possesses both the know-how in urban transport planning and the construction of rolling stock and transport infrastructure. Poland can therefore play a key role in designing the metro network in Baghdad, Mosul, Erbil, and other cities, as it has recent experience in this area. In particular, it can share the expertise of companies like Metroprojekt, which was the main designer of the Warsaw Metro. This experience is recent, as the Warsaw Metro is under continuous expansion. Furthermore, the design of the metro in Warsaw takes into account complex underground conditions and is being implemented in a highly built-up area with heavy traffic. It is precisely this kind of experience that Iraq needs to realize its metro construction plans. Poland can also help reform the entire public transport system in Baghdad and other Iraqi cities and introduce city buses and trams. Poland also has very great planning and design experience in this field. Specifically, Poland can offer advice on creating modern public transport authorities that are independent of local government and responsible for fare and timetable integration (buses, trams, metro). The offer may also include training for engineers and planners on optimizing the transport network and implementing passenger information systems (display boards, applications), as well as launching student and engineer exchange programs with the Warsaw University of Technology and the Cracow University of Technology to train local specialists in metro construction, tunneling, and traffic management. Poland can also present a broad offer in the field of supplying modern rolling stock that is competitively priced and adapted to difficult conditions. Poland is a leader in this area. This includes Solaris buses, which is a leading city bus manufacturer in Europe and has introduced low-floor buses to cities in Poland and Europe. Solaris is also a leader in the segment of electric and hydrogen buses, which corresponds to global trends. The number of electric vehicles is also growing rapidly in Iraq. The Polish bus offer includes both city and intercity buses, with other manufacturers being Autosan and NesoBus. The former, besides city buses, also offers medium-sized intercity buses, ideal for short routes. NesoBus, in turn, offers modern hydrogen buses. Iraq should also consider introducing trams to its cities. Although this means of transport is not very popular in the Middle East, some countries, such as Turkey, Qatar, and the United Arab Emirates, have been expanding their tram lines in cities for many years. It is worth noting that at the end of the 20th century, there was a trend considering the tram as an outdated means of transport, and many lines were liquidated. This happened both in Poland and Iraq. However, for more than a dozen years, the opposite trend has prevailed, and many tram sections in Poland that were liquidated just a dozen years earlier have been rebuilt, and new ones have also been created. Currently, the length of tram lines in Poland is over 2400 km, and the tram network in Warsaw and the Katowice agglomeration are among the largest and most modern in Europe. Poland can therefore present a very broad offer in this case as well. Warsaw can share its experiences with Baghdad in the construction of modern lines in the city center, including underground sections and interchanges, such as the line currently being built connecting the West Station (Dworzec Zachodni) with the center. Polish companies Modertrans and Pesa can offer the most modern tram rolling stock, which can now be seen in many European cities, including Germany, Romania, Bulgaria, Hungary, Ukraine, Estonia, and Slovakia. Polish companies also have extensive experience in the construction of tram tracks and accompanying infrastructure and have carried out contracts in this regard in Germany, Lithuania, Slovakia, and Latvia, among others. An urgent need for Iraq is also the modernization and expansion of the railway network. Currently, the only active railway line connects Basra with Baghdad, but it requires urgent modernization. A 100 km section from Baghdad to Ramadi has also been operating for a year. Meanwhile, the ambitious Iraqi Development Road project, which is to connect the new Grand Faw Port on the Persian Gulf with Europe via Turkey, requires the creation of a modern railway line. Turkey has been expanding and modernizing its railway network for many years, and only a 150-kilometer section from Kurtalan needs to be built to connect it to the Iraqi border. However, Iraq must rebuild its railway network, especially from Baghdad to Mosul, and then build a new section to the border with Turkey. This, however, is only the first step, as it is also necessary to connect other cities in Iraq, including the Kurdistan Region, with the railway network. It is also known that the Iraqi authorities attach great importance to this, and in June 2025, World Bank financing of $930 million was announced for the Iraq Railways Extension and Modernization (IREM) project, which will modernize the Mosul – Umm Qasr line, totaling 1047 km. Poland is an ideal partner for the implementation of this project, as it has vast experience in modernizing railway lines and capabilities in the production of railway rolling stock and the construction of infrastructure, including traction and trackage, as well as modern railway stations. Over the last 10 years, Poland has allocated about $25 billion to the modernization of approximately 9,000 km of tracks, resulting in reduced travel

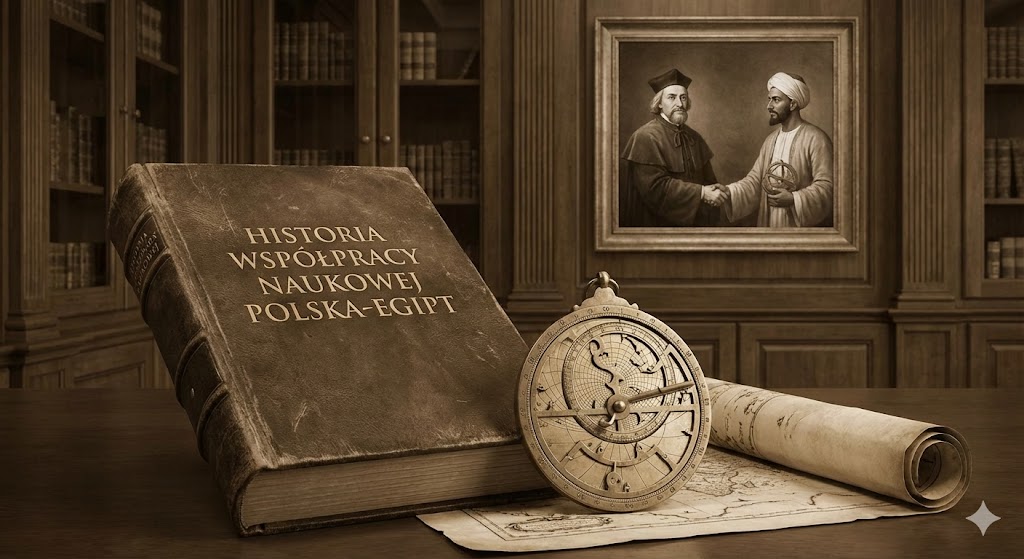

Community of Knowledge. Centuries-old scientific cooperation between Poland and Egypt

For more than three centuries, Poland and Egypt have remained in a unique relationship in which science, discovery and respect for heritage create a lasting bridge between Europe and the Arab world. Despite geographical distance and differing cultural traditions, the two nations met in the realm of knowledge. It is a long history of collaboration among scholars who shared the conviction that knowledge transcends political, religious and linguistic boundaries. Although formal academic cooperation emerged only in the twentieth century, its roots reach back to the seventeenth century, when the first Polish accounts from Egypt had a cognitive, religious and travel-related nature. Over the following centuries the forms of these contacts evolved—from descriptions and clerical missions, through the work of military engineers and orientalists, to joint archaeological research, scholarship programmes and digital archives of cultural heritage. This history demonstrates that science constituted the most enduring language of dialogue between Poles and Egyptians, regardless of borders, political systems or historical contexts. It was precisely in the sphere of knowledge, discovery and education that a unique bond between the two nations developed—a bond grounded in curiosity about the world, mutual respect and a shared desire to understand the civilization of the other. And it is worth emphasising that scientific and intellectual relations between Poland and Egypt are among the oldest and most enduring in the history of contacts between Central Europe and the Arab world. The earliest references to the presence of Poles in Egypt date back to the late seventeenth century. Their activity at that time was primarily missionary and religious in nature, but their accounts and correspondence also contained valuable geographical, ethnographic and natural observations. In the second half of the seventeenth century, missionaries, scholars and clergy from the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth travelled to the Levant and further towards Africa, combining religious aims with natural and social observations. A note dating from the late seventeenth century mentions Brother Paweł from Małopolska, who on 2 July 1695 appeared in Alexandria as part of missionary work. In the eighteenth century these missions assumed a more organised character. Sources record the activity of Jan of Poland (from 13 April 1711), Kazimierz Nerlich from Silesia (who died in Cairo in April 1718), Jan Kryspin Sobach from the Greater Poland province (around 1720), Andrzej Jordan (1755) and Antoni Burnicki (1762–1763) from the Lithuanian province. The latter left valuable notes on Alexandria, its monuments and customs, mentioning, among other things, the “Cleopatra’s Needles” and Pompey’s Column. Although missionaries were not scholars in the modern sense, they carried out systematic observations of nature, climate and language, recording them and creating the first seeds of Polish scholarly reflection on the Arab world. The Napoleonic expedition and the birth of Polish–Egyptian scientific cooperation Napoleon Bonaparte’s expedition to Egypt in 1798 opened a new chapter in the history of Polish-Egyptian contacts, linking science with politics and military affairs. Poles, both officers and engineers, served in the Army of the Orient and played an important role in organising the research expedition that accompanied the campaign. Among them was Józef Sułkowski, Napoleon’s aide-de-camp, regarded as one of the first Poles to participate in a scientific-exploratory enterprise on Egyptian soil (he was assigned by Napoleon to civil duties at the Egyptian Institute, an academy of sciences based in Cairo). Alongside him worked Józef Szumlański, who recorded observations about Egypt’s population, local customs and, in particular, its monuments in a short work titled The Egyptian Expedition of 1798. Also noteworthy is Józef Feliks Łazowski, who first became known for fortifying Khotyn, Akkerman on the Dniester, and Izmail on the Danube. In Egypt, as head of the brigade of engineers, he produced a map of the province of Al-Minufiyya in Lower Egypt, correcting errors found in the earlier map of Egypt by J. B. d’Anville, especially in the Nile Delta region. In 1800, Łazowski took part in preparing a topographical map of Egypt, later published in Paris. He was among the advocates of building a navigable canal through the Isthmus of Suez, at a time when the remains of the ancient “Canal of the Pharaohs” were still clearly visible. The Bonaparte expedition corps in Egypt also employed an outstanding orientalist and polyglot, Zalkind Salomon Hurwicz (1740–1812), a Polish Jew most likely from Lublin. Napoleon appointed him head of the Arabic printing house and periodicals, as well as the French school in Cairo. Emigrants, engineers and builders of modern Egypt (19th century) After the collapse of Poland’s national uprisings in the nineteenth century, Egypt became a refuge for Polish engineers, technicians and military officers, who found there not only safety but also the opportunity to work in accordance with their education and scientific ambitions. In Egyptian archives, as well as in Polish émigré sources, traces of their activities have been preserved, covering both military and civilian projects. Among them were Julian Duszyński, a cavalry instructor in the Egyptian army around 1840, and Ignacy Ciszewski (1875–1924), a graduate of the Institute of Railway Engineers in St. Petersburg, who was sent to Egypt by the administration of the Astrakhan Railway to study the structural solutions of bridges in the Nile Delta. The knowledge he acquired in Egypt was later applied in the construction of a bridge over the branches of the Volga. Of particular significance was the work of Lieutenant Tomasz Bartmański, an engineer who discovered the remains of the ancient canal linking the Nile with the Red Sea. He also took part in an expedition organised by Muhammad Ali to the Mountains of the Moon and the sources of the Nile. Researchers, naturalists and Egyptologists – science as a bridge between cultures In the second half of the nineteenth century, the Polish scientific presence in Egypt began to take on a more systematic form. Poles participated in natural, linguistic and archaeological expeditions conducted in the spirit of international cooperation. Among them were Aleksander and Konstanty Branicki, organisers of zoological expeditions (1863–1874) with the participation of Henryk Dziedzicki and Antoni Waga. Their research carried out in Egypt and Nubia

Poland–Egypt: A shared future and partnerships in key sectors

Poland and Egypt are linked by long-standing, friendly relations whose beginnings date back to the establishment of diplomatic ties in 1927. Egypt is considered a key partner for Poland in the Arab world, both politically and economically. In recent years, intensive high-level contacts have given this cooperation a new dynamism. Faced with global challenges, both countries are jointly seeking new areas of cooperation that will bring tangible benefits to their societies and support the stability of the region. Below we present the prospects for developing partnership in key sectors. Economic and trade cooperation A growing scale of economic cooperation – with potential for more: In recent years, trade between Poland and Egypt has increased significantly, surpassing USD 900 million in 2022. The structure of this exchange, relatively balanced and complementary, provides a solid foundation for further intensification. Poland offers Egypt machinery, equipment, food products and industrial components, meeting the growing consumption and modernisation needs of a 110-million-strong market. Egypt, in turn, supplies Poland with high-quality textiles, cotton and agricultural and tropical products that the Polish market does not produce in sufficient quantity. Strengthening logistical links, investment and supply chains—also within cooperation with the Egyptian Suez Canal Economic Zone (SCZone)—may in the coming years transform trade relations into a lasting industrial partnership based on investment and joint processing. Investment as a lever of development partnership: The resumption, after 30 years, of the Polish–Egyptian Joint Commission for Economic Cooperation marked a new phase in investment relations. Sixteen priority sectors were identified – from ICT and green energy to smart cities – giving the cooperation a strategic direction. An example of this new quality is the investment by Feerum in a factory for grain storage and drying equipment in the Port Said economic zone. This project not only strengthens Poland’s industrial presence in Egypt but also supports Cairo’s key goal of increasing food security, serving as a model for possible Polish specialisation in agricultural technologies supporting Egypt’s food-sector transformation. In the coming years, the development of joint projects within Egypt’s mega-infrastructure initiatives, such as the new administrative capital or the modernisation of the railways, as well as the creation of lasting institutional links (including cooperation between economic zones), will make it possible to transform Polish–Egyptian relations from transactional to systemic. Egypt gains a partner from the EU; Poland gains a gateway to the Middle East and Africa. Economic development as a shared strategic platform: Both sides see significant potential in further expanding trade and investment, with the emphasis shifting from the exchange of goods to the building of durable sectoral linkages. Egypt plans to increase exports of strategic raw materials (fertilisers, petrochemicals, building materials), responding to the needs of Polish industry and price stability. Poland, as a supplier of advanced agricultural technologies, machinery and food products, fits naturally into Egypt’s plans to enhance food security and develop processing within the “1.5 million feddans” programme. In July 2025, discussions took place between the Ambassador of the Republic of Poland and Egyptian officials responsible for this project, during which concrete areas of cooperation were examined, including mechanisation, smart agriculture and processing. Poland can support this process not only with equipment but also through the transfer of know-how, the creation of research and implementation centres and the training of specialists. Trade and investment missions in sectors such as modern construction, infrastructure, rail transport, digital technologies and logistics will be crucial. In the longer strategic horizon, Poland may become for Egypt a technological and food-security partner, while Egypt may serve as a distribution platform for Poland in Africa and the MENA region. New technologies and cybersecurity Digital transformation as an impulse for technological cooperation: Poland and Egypt view digitalisation as a strategic pillar of their economic modernisation. Egypt is implementing ambitious digital projects, for example building 14 fourth-generation cities, including the New Administrative Capital, and developing e-government services and intelligent transport systems. Poland, with advanced competencies in digital administration and cybersecurity, agreed during the visit of the President of the Republic of Poland in 2022 to intensify the exchange of experience in this field.Potential areas of cooperation also include the localisation of Polish technologies in Egypt, the development of joint IT projects and support in creating infrastructure for digital services. Polish ICT companies, such as Comarch, are already expanding in Middle Eastern markets, and Egypt—being a large market with a growing demand for smart-city and e-government solutions—is becoming a natural next direction for this expansion. Cooperation in this sector has long-term potential, encompassing technology transfer, workforce training and the creation of an innovation ecosystem supporting the digital transformation of both countries. Cybersecurity as a shared strategic priority: As Poland and Egypt develop their digital economies, they are increasingly focusing on challenges related to critical infrastructure security, data protection and countering disinformation. With the growing digitalisation of public, financial and healthcare services, cooperation in this area is gaining strategic significance. Poland, as an active participant in EU and NATO initiatives, has well-developed competencies in building national cybersecurity strategies, responding to incidents and implementing data protection standards. Egypt, in turn, is expanding its institutional and legal capacities and seeking partners for knowledge exchange and workforce development. In the future, deeper cooperation is possible within training programmes, expert consultations and academic and research projects, covering areas such as artificial intelligence, cryptography and the security of public administration systems. Investing in this cooperation today is not only an element of shared digital security but also a catalyst for developing a modern technological sector within Polish–Egyptian relations. Defence and security cooperation A partnership for stability: Poland and Egypt consistently build their image as pillars of stability in their respective regions — Central and Eastern Europe and the Middle East. Shared interests in security, counterterrorism, combating extremism and preventing the destabilisation of neighbouring regions will, in the future, require deeper operational and political cooperation. Egypt, which plays a key role in the eastern Mediterranean and is active in stabilisation efforts in the Sahel region, remains a strategic point of reference for Poland

Poland and Lebanon – a partnership for the prosperity of both nations

At the end of 2025, economic relations between Poland and Lebanon can be described as partnership-based and steadily developing. Although the two countries are separated by geographical distance, they are connected by a rich history of contacts and growing cooperation – from humanitarian activities to trade and investment. These relations are built on pragmatism, mutual benefits and trust, which give them a stable and long-term character. Beginnings of diplomatic and economic relations The history of official contacts between Poland and Lebanon dates back to the interwar period. From 1 November 1933, consular agents of the Republic of Poland operated in Beirut, responsible for trade and maritime affairs in the territory of Lebanon and Syria. This was the first permanent Polish representative body in the region, established primarily to support economic exchange and protect the interests of Polish enterprises. Other administrative and civil matters at the time remained under the jurisdiction of the Polish Consulate in Marseille. With the growing importance of Beirut as a centre of trade and maritime communication, in 1939 a Vice-Consulate of the Republic of Poland was established in the Lebanese capital, and on 1 April 1940 it was transformed into the Consulate General of the Republic of Poland. On 15 December 1943, the Polish Consul General in Beirut simultaneously obtained accreditation to the government of Lebanon as a diplomatic agent of the Polish government-in-exile in London, with the rank of Minister Plenipotentiary. The formal establishment of diplomatic relations between Poland and Lebanon took place on 1 August 1944, marking the culmination of a long process of building Poland’s presence in the region. It is worth emphasising that the activity of the Polish consular service in Beirut from the 1930s onward focused not only on diplomatic issues but also on economic matters, supporting maritime trade, the export of goods and the development of business contacts between the two countries. Trade – from Polish apples to Lebanese olive oil Economic cooperation between Poland and Lebanon has clearly revived in recent years. After a period of stagnation linked to Lebanon’s economic crisis, trade has regained momentum. In 2018, for the first time in a decade, trade turnover exceeded USD 100 million, and in 2024 Polish exports reached nearly USD 96 million, confirming the stable potential of the market despite difficult macroeconomic conditions. Poland exports to Lebanon a diversified range of goods: from machinery, equipment and household appliances to agri-food products, industrial goods and construction materials. Among the most significant items are gas turbines, tyres, cheeses, meat, cereals and live cattle. Lebanon, in turn, exports far less to Poland—its exports in 2019 amounted to around USD 13 million—but they are specialised, high-quality products such as natural casings for the meat industry, electrical cables, olive oil, wines and fresh fruit. The trade exchange is asymmetric, with Poland maintaining a positive balance for years. At the same time, cooperation is developing in a spirit of mutual benefit. Poland, known for its exports of food, furniture and construction materials, finds in Lebanon an absorptive market, particularly in the food sector. Due to limited agricultural land, Lebanon imports most of its food, creating a stable demand for Polish apples, dairy, meat, cereals and processed agricultural products. There is also cooperation potential in the construction and energy sectors. Lebanon’s reconstruction and infrastructure modernisation programmes following periods of crisis open opportunities for Polish producers of ceramics, fixtures, building joinery and thermal-insulation technologies. Poland, with experience in energy efficiency, can support Lebanon’s efforts toward energy savings and sustainable construction. Trade between both countries is becoming increasingly two-directional. Poles are beginning to appreciate Lebanese products and cuisine, as evidenced by the growing number of Lebanese restaurants in Polish cities. Lebanese food products—especially wines, olive oil, spices and fresh fruit—are appearing more frequently on the Polish market. It is precisely in the latter category that particular potential lies: Lebanese strawberries, figs, grapes and citrus fruit, which ripen almost year-round, could reach Poland outside the domestic harvest season. Such an expansion of imports not only enriches the offer for Polish consumers but also supports Lebanese agriculture, making trade cooperation beneficial both economically and socially. Investments and business – capital flows in both directions Not only trade but also investments today build a bridge between Warsaw and Beirut. Although before 2020 Polish direct investments in Lebanon were symbolic (only around USD 0.1 million at the end of 2018), which resulted from business caution toward the region’s instability, Lebanese capital had long been seeking opportunities abroad—traditionally in Francophone countries, the USA or the Gulf, but part of these funds also reached Poland. Lebanese investments in Poland, though modest (around USD 15 million in 2018), are concentrated in the agri-food sector (e.g., food processing, trade in exotic products), the paper industry, and even hospitality and gastronomy. In Polish cities one can come across restaurants run by Lebanese entrepreneurs, tempting with the aroma of roasted lamb and spices from the Middle East. These are small but vivid accents of Lebanese business presence along the Vistula. One of the success stories is Technica, a family-owned Lebanese company producing modern industrial lines for global brands. In 2019 Technica decided to open its European headquarters precisely in Poland. Why? “We chose Poland because you have truly competent people with business intuition here. Compared with other European countries, Poland is cost-attractive and is located in the centre of the continent,” explains Cynthia Abou Khater from Technica’s management board. This investment is an example of the interpenetration of capital and know-how. The Lebanese company benefits from Poland’s location and workforce, creating jobs for Poles, while at the same time contributing its international experience and network of contacts. Such examples show that the potential for investment cooperation is only beginning to unfold. With an improvement of the situation in Lebanon in the future, one may expect greater interest from Polish companies in participating in infrastructure projects in the country, whether in rebuilding the power grid or modernising the water management system. Already in 2018, during the donors’ conference, Poland

Poland and Lebanon – a history of friendship and cultural dialogue

Poland and Lebanon share a surprisingly rich history of contacts. Over the centuries, spiritual, artistic and social ties have deepened, creating an inspiring picture of mutual cultural interpenetration. From medieval pilgrims, through Romantic poets, missionaries and wartime refugees, to the contemporary Polish community in Lebanon, these histories form a narrative of hospitality, shared values and friendship between the two nations. Historical encounters: from pilgrims to Romantics The first mentions of Poles in Lebanon date back to the time of the Crusades. Although Polish knights did not take part in the crusades on a large scale, we know that already in the 13th and 14th centuries Polish nobles and pilgrims reached Lebanese lands on their way to the Holy Land. One of the pilgrims whose valuable notes describe his journey through Lebanon was Prince Mikołaj Krzysztof Radziwiłł “Sierotka”, who travelled to the Holy Land in 1582–1584, recording his passage through Tripoli, the cedar forests and the snow-covered peaks of Lebanon. Another important chapter in cultural relations between the two countries was the journey of Juliusz Słowacki. In 1837 the great Polish poet visited Beirut, Tripoli, and the Maronite mountain monastery of St. Anthony in Ghazir. It was there, “in the land of cedars”, that the poet sketched the first version of Anhelli, one of the masterpieces of Polish Romanticism. In letters to his mother Słowacki expressed his admiration for Lebanon, writing about its astonishing landscapes and the spiritual atmosphere of the place. Years later he even confessed in his diary: “I would like to find myself in Lebanon again.” His stay in the Lebanese monastery proved transformative both as an artist and as a person. It was in Ghazir that Słowacki experienced a profound spiritual renewal and, influenced by a Polish Jesuit he met there, made a confession that lasted all night (on Holy Saturday in 1837) and reconciled himself with God. This mystical experience in Lebanon forever marked the poet’s work and became a bridge between cultures. The Jesuit who influenced Słowacki’s fate was Father Maksymilian Stanisław Ryłło, a Polish Jesuit, traveller and papal emissary. Born in 1802 in the eastern territories of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, Father Ryłło travelled widely in the Middle East and acquired deep knowledge of the Arabic language and Arab customs. For this reason, in 1836 he was sent by the Vatican on a mission to establish contact with the Eastern Christian Churches and to found a school in the Middle East. Through his efforts the Asiatic College (Collegium Asiaticum) was established in Beirut in 1839. This institution played a pioneering role in higher education in the Middle East. In 1875 the College was transformed into Saint Joseph University (Université Saint-Joseph, USJ), which today is one of the oldest and most prestigious universities in the region. Significantly, USJ continues to remember its Polish founder: on the 100th anniversary of Father Ryłło’s death, in 1948, a commemorative plaque was unveiled in the university building in his honour. Father Ryłło also made contributions to the local community, as in 1839 he donated to the Church of Our Lady of Deliverance in Bikfaya an icon of the Virgin Mary painted at his request by an Italian artist. The painting still hangs in the church today, serving as a living monument to the interweaving of cultures in Lebanon. Poles in the spiritual and social service of Lebanon Polish–Lebanese cultural relations are not only the individual stories of poets and clergy, but also a broader involvement of Poles in the life of the land of cedars. In the 19th century, many Polish patriots, after the fall of national uprisings, sought refuge and opportunities to continue their struggle for freedom alongside allies in the Ottoman Empire. Turkey readily accepted experienced Polish officers into its army, and some, such as General Józef Bem, even converted to Islam to be able to serve in the Sultan’s forces. In this context, one particularly significant episode was the mission of Michał Czajkowski, known as Sadyk Pasha. This Polish émigré in the service of the Sultan in 1860 took command of units sent to Lebanon to protect the local Christians (mainly Maronites) from persecution during the violent clashes with the Druze. In the years that followed, additional Polish military formations composed of Christian soldiers were deployed to Lebanon. In 1865 an entire cavalry regiment, consisting largely of Poles, was established. In recognition of its merits, it was incorporated into the Sultan’s Guard and assigned to service in Lebanon, where it operated for 24 years. All the officers of these units were Poles, and their uniforms and banners referred to Polish colours. Poles safeguarded the security of Lebanon’s Christian population, which, as a result, could more actively restore trade routes along the Mediterranean coast. It is also worth mentioning the son of Michał Czajkowski – Władysław Czajkowski, who served as the governor of Lebanon under Ottoman rule between 1902 and 1907. During that time he bore the title Muzaffar Pasha. Although his administration did not introduce spectacular reforms, the very fact that such a high administrative function was entrusted to a Polish émigré testifies to the trust that Poles enjoyed in the region. Wartime fates: Polish refugees welcomed by Lebanese hospitality (1943–1950) One of the most moving chapters in Polish–Lebanese relations is the story of Polish refugees during the Second World War. After the signing of the Sikorski–Majski Agreement, thousands of Poles, including women and children, travelled south in search of refuge alongside the Allies. Between 1943 and 1946, around 6,000 Poles evacuated from the Soviet Union reached Lebanon via Persia. The Lebanese government, despite its own difficulties, recognised the Polish newcomers as official allies and agreed that the Polish diplomatic mission would assume care for the refugees. Thus began a remarkable period of Polish presence in Lebanon, one whose defining elements included vibrant cultural life. The refugees were initially housed in a temporary camp in Beirut, but soon many were settled in hospitable mountain towns whose names still evoke deep emotion among Polish families. In these

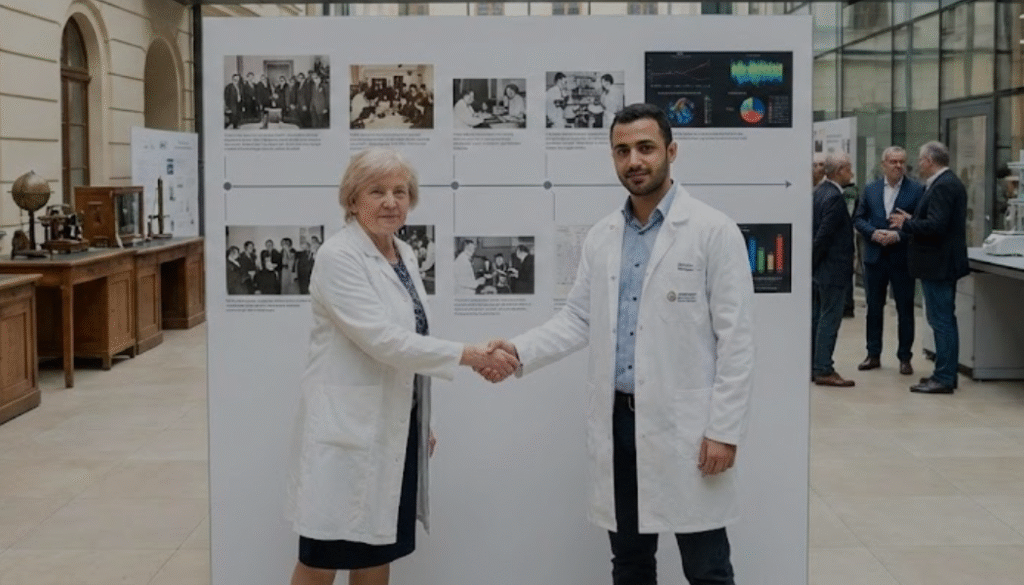

Polish-Lebanese scientific cooperation – tradition and modernity

The scientific traditions linking Poland and Lebanon have a long history, dating back to the first half of the nineteenth century. Their beginning was the work of the Polish Jesuit Father Maksymilian Stanisław Ryłło, an outstanding missionary and scholar who played a key role in the development of education in the Middle East. In 1839, on his initiative, the Asiatic College (Collegium Asiaticum), a Jesuit school, was established in Beirut, which in 1875 was transformed into Saint Joseph University (Université Saint-Joseph, USJ). It was the first modern institution of higher education in the region and at the same time a symbolic beginning of the presence of Polish educational thought in Lebanon. The work of Father Ryłło, who knew the Arabic language and the culture of the Middle East, left its mark not only on the history of education but also in the memory of the local community. USJ still commemorates its Polish founder, and one hundred years after his death, a memorial plaque dedicated to him was unveiled in Beirut. From the same period dates another thread of Polish-Lebanese intellectual ties: the visit of Juliusz Słowacki in 1837. In the monastery in Ghazir, the poet created the first version of Anhelli, a work inspired by the spiritual atmosphere of Lebanon. This meeting of cultures and ideas became one of the first links from which a lasting tradition of scientific and cultural dialogue between the two countries would eventually grow. Archaeology and heritage protection Since the 1990s, Polish-Lebanese archaeological cooperation has been developing dynamically. Since 1996, archaeologists from the University of Warsaw, in cooperation with Lebanese partners, have been conducting regular excavations in the ancient settlements of Khirbet Chim and Jiyeh (Porphyreon) on the Phoenician coast. Over more than twenty research seasons, the Polish mission has uncovered the remains of two well-preserved settlements from the Roman and Byzantine periods, including houses, a Roman temple, early Christian churches with mosaics, and an olive press. These discoveries have provided valuable knowledge about daily life and the economy of ancient Lebanon. In parallel, conservators from the Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw restored hundreds of square meters of mosaics and wall paintings, saving many monuments from destruction. The achievements of this cooperation were honored with the exhibition “People, Places, Monuments. 20 Years of Polish-Lebanese Cooperation in Archaeology and Conservation (1996–2016)”, organized in Beirut by the Polish Centre of Mediterranean Archaeology of the University of Warsaw, the Embassy of the Republic of Poland in Lebanon, and the French Institute. Support for education and scientific infrastructure Contemporary scientific cooperation between Poland and Lebanon includes not only research but also concrete development activities. Lebanon is one of the priority countries of the Polish Aid program, under which projects supporting education, school infrastructure and public safety have been implemented for several years. One of the key areas is the modernization of educational institutions. In many schools, solar panels have been installed to ensure a stable supply of energy despite the ongoing energy crisis. At the Saint Sauveur School in Jeita, solar batteries were installed on the roof, and a modern science laboratory equipped with professional experimental tools was created at the same institution. As a result, older students can learn through practice and develop skills needed in a modern economy. An important component is also counteracting digital exclusion. At the Foyer de la Providence educational center in Beirut, which cares for orphaned and vulnerable children, both mobile and stationary computer labs were created. They gave students access to modern technologies and improved the quality of education. Poland also supports infrastructure and public safety. At civil defense stations in Beirut, water, sewage and electrical systems were modernized, and solar lighting was installed. In cooperation with the Polish foundation IHelp Institute, personnel of the Civil Defense, the Red Cross and the fire department were trained, receiving equipment and improving their operational readiness.As part of inclusive education projects in northern Lebanon, in the town of Zagharta, a culinary workshop was created for children and adults with autism, helping them develop practical life skills. Meanwhile, in cooperation with Polish Humanitarian Action, a training center in Beirut’s Tajjune district was supported, offering vocational courses for women and youth. Such broad initiatives show that Poland actively supports the development of human and scientific capital in Lebanon. Improving learning conditions—from providing energy and equipping schools to vocational training—translates into real opportunities for the young generation of Lebanese citizens. Academic partnerships and student exchange One of the most important pillars of scientific cooperation between Poland and Lebanon is the direct academic and research contacts. Polish universities are increasingly establishing partnerships with Lebanese institutions, which supports the exchange of knowledge, experience and best practices. An example of such cooperation is the agreement between the Faculty of Architecture of the Cracow University of Technology and the Lebanese American University. Joint architectural projects allow students and lecturers from both universities to benefit from different experiences and engineering traditions, creating modern design solutions inspired by both European and Middle Eastern heritage. In the field of social and political sciences, cooperation between the Polish Institute of International Affairs (PISM) and the Issam Fares Institute for Public Policy and International Affairs at the American University of Beirut is becoming closer. Joint research, seminars and expert exchanges focus on the analysis of international politics and security in the Middle East region. At the same time, the number of Lebanese students taking advantage of educational opportunities in Poland is growing. The Polish government offers young people from Lebanon participation in prestigious scholarship programs, especially in technical, natural and IT fields. One of the most important is the Stefan Banach Scholarship Programme, implemented by the Polish National Agency for Academic Exchange (NAWA), which enables outstanding students from Lebanon to undertake free master’s studies in Polish or English at Polish universities. Thanks to such initiatives, successive generations of Lebanese graduates of Polish universities become natural ambassadors of Polish science and culture in their country, strengthening academic ties and building lasting bridges of cooperation for the

Mosul – Reconstruction and Security

On 2nd of November a conference dedicated to the Iraqi information environment and the threats of disinformation and foreign influence operations was held at the University of Mosul. This conference was organized by the Info Ops Foundation as part of a project researching Iraq’s information environment, carried out in cooperation with the Casimir Pulaski Foundation. The aim was both to present the results of our research and to learn the reflections of the local academic community on them. The development of scientific cooperation between Iraqi universities, such as the University of Mosul, and Polish universities is extremely important for developing mutual relations, better understanding, counteracting disinformation and extremism, and, as a result, building a secure international environment. Science and education are, after all, the opposite of ignorance and fanaticism, which various types of extremists and terrorists feed on. Mosul is the best example of this. This was my second visit to Mosul, but under such different conditions. As I was driving through one of the large roundabouts, an image of it from a few years ago, when I was there for the first time, returned to me. At that time, the remnants of a large banner with the symbols of Daesh (ISIS) terrorists were hanging from one of the buildings. Everywhere there was destruction and rubble, and one, great tragedy for the inhabitants. It all began in June 2014, when a horde of several hundred Daesh terrorists conquered Iraq’s second-largest city in just 3 days. This was possible because the conflict between the Sunni population and the Shiite security forces had undermined the population’s trust in the authorities, causing them not to resist the invaders. It was a classic cognitive error, proof of how important education in information and cognitive security is. The terrorists exploited the moods and emotions of the residents to deceive them. The local Sunnis did not want to murder Shiites or destroy churches, but this was exactly what the terrorists did. They also did not want the destruction of science, education, and cultural heritage, but Daesh brought exactly that. By the time the residents realized that terror awaited them, it was already too late. The period from June 2014 to July 2017 is the darkest chapter in the city’s history, including its university and its library. A reign of terror, during which most students and academic staff fled, and the gigantic university complex was looted and then transformed into a bomb and chemical weapons factory. Library collections that could not be hidden from the barbarians were destroyed. In October 2016, the 9-month battle for the liberation of Mosul began. It was then, in the spring of 2016, that I came to Mosul for the first time. It was one great ruin, as the fighting took place over literally every house. After the fall of Daesh, the city’s reconstruction began, and today it is hard to believe that such infernal scenes took place there just a few years ago. Under the rule of the current governor of Nineveh, Abdul Qader al-Dakhil, Mosul has become a very safe city, where groups of tourists, including from Europe, are once again walking. And there is much to see here. Mosul is a very old city, with a history dating back to 6,000 BC. In the times of the Assyrian Empire, its capital, the city of Nineveh, was located there, the archaeological remains of which are preserved to this day. In the first millennium AD, Christianity developed in the city, followed by Islam. Many historical monuments also remain from this period, which, however, Daesh tried to destroy. Many churches were razed to the ground, but today crosses are once again visible in the city’s skyline. The terrorists, despite calling themselves the “Islamic State,” also destroyed mosques, as they disliked that many of them contained the tombs of prophets and other holy men from both Christianity and Islam. This is why, in the final days of the war, Daesh blew up the Great Mosque of al-Nuri, even though it was there that Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi declared himself “caliph” in 2014. The reason was that this 12th-century structure contained the tomb of Ali al-Asghar ibn al-Hanafiyyah. This mosque is famous for its leaning minaret (a result of wind effects), which has been rebuilt from its original materials. Thanks to the good governance of the city and province by the current governor, Abdul Qader al-Dakhil, Mosul does not look as if a cataclysm has passed through it. Importantly, supporting the University of Mosul, which has also gotten back on its feet, is of particular significance to Dakhil. It is hard to believe that just a few years ago, terrorists embedded there transformed it into a factory of death. Today, over 60,000 students of both genders study in this gigantic complex. A special place is the library, which is still rebuilding its collections after the Daesh conflagration. Many valuable books were saved, but their condition was deplorable. However, the University of Mosul Library effectively applied the most modern conservation techniques and also digitized its collections. This is one of the important areas where cooperation with Polish universities and libraries is possible. The University of Mosul’s access to our collections will help counter the resurgence of extremism, as it stems from ignorance. On the other hand, it is also important for Europeans, including Poles, to be more familiar with Iraqi scholarly achievements. During the visit to the University of Mosul, which also included a meeting of the Info Ops Foundation delegation with Governor Abdul Qader al-Dakhil, the prospects for scientific and academic cooperation between Iraqi universities, particularly the University of Mosul, and Polish universities were discussed. The Info Ops Foundation intends to mediate in the development of joint scientific projects. The main event during the visit was the conference on disinformation, which discussed, among other things, issues related to the distortion of the image of Europe, including Poland, in Iraq, in connection with problems such as migration, the war in Ukraine, and the Palestinian issue.

Lebanon in Times of Crisis: Citizen Resilience, International Solidarity, and the Challenges of Disinformation

In times of crisis, states naturally rely on the resilience of their citizens and the solidarity of the international community. Just as individuals turn to friends in difficult moments, and companies seek partners during uncertainty, Lebanon has received over $12 billion in international aid since 2019. This support has enabled hospitals to function, children to access education, and food and clean water to reach families in need, saving the most vulnerable lives. Of course, this aid is not without challenges: coordination gaps, transparency concerns, and unequal distribution of resources exist. However, focusing solely on these shortcomings has created space for disinformation, which diminishes the significance of aid, undermines the intentions of donors, and weakens trust at a time when Lebanon needs unity more than ever. As President Michel Aoun highlighted in his inaugural vision:“My commitment is to open Lebanon to both worlds, East and West, to build alliances and strengthen Lebanon’s external relations […] to preserve Lebanon’s sovereignty and its freedom of decision-making.”In this spirit, international support, despite its imperfections, remains essential, and we cannot allow disinformation to undermine it. Disinformation poses not only an internal threat but also affects Lebanon’s social fabric and foreign relations. Humanitarian aid is increasingly portrayed as foreign interference, raising doubts between Lebanon and its allies. This undermines trust and risks isolating the country from partners stepping in during crises. As experts note:“We create dreams and bring them to life, and regardless of our differences, in times of crisis we support each other, because if one of us falls, we all fall.”Countering disinformation is crucial to protecting internal unity and the credibility of partnerships. As individuals, we have a responsibility to pause, verify, and ask questions before sharing information. One example is the fake organization International Organization for Human Rights and Refugee Affairs, which claimed in Aleppo that it had signed a $10 million aid agreement. It used stolen UN logos, manipulated images, and staged media reports. Its real goal was never to provide aid but to create the appearance of legitimacy for the Assad regime and undermine trust in real international assistance. Effective disinformation blurs the line between truth and falsehood, causing people to doubt reality and take opposing sides. Lebanon’s strength lies in unity and resilience, and protecting that unity means exposing lies before they create divisions. Disinformation does not always take the form of fake news—it can also appear as fake honors or false titles. The same fraudulent organization once appointed a Syrian artist as a UN Goodwill Ambassador for Women, using a title that appeared international but had no UN documentation. Such staged recognitions and media tricks aim to inflate false credibility, divert attention from real humanitarian aid, and confuse public opinion. Lebanon is undergoing a governance crisis that requires a shift in political perception to maintain security. Disinformation thrives where government fails, making its detection and exposure critical for Lebanon’s future. Another wave of disinformation concerned aid from the United Arab Emirates, falsely claiming that aid shipments were “equipped with spyware” intended for surveillance rather than support. Posts and memes used fear-inducing language and manipulated images of aid boxes to suggest that even food and medicine were tools of espionage. This turns solidarity into suspicion, undermines trust in humanitarian partners, and distances Lebanon from its allies. In reality, such rumors deepen divisions and risk isolating the country at a time when cooperation and external support are essential for survival. As experts remind us:“Our unity guarantees our security, and our diversity enriches our experience.” There is no security without unity. For years, Poland has supported Lebanon not only with words but also through long-term humanitarian programs that bring real change: In times of crisis, Lebanon’s strength lies in unity, citizen resilience, and international cooperation. Protecting this unity requires not only real humanitarian aid but also a conscious fight against disinformation—pausing, verifying facts, and questioning information before sharing. This is key to maintaining Lebanon’s security, stability, and future.